Chapter Nine - Work

I. Reading

I am Matsushita

We’ve already examined how many underlying cultural differences are reflected in the different ways we speak. Talking about jobs is another example. When adults meet for the first time, their occupations are one of the first topics discussed, regardless of culture. Take a look at the following conversations:

Harry: Hi, my name is Harry.

Dave: Nice to meet you Harry, I’m Dave. Dave Herman.

Harry: Nice to meet you Dave. What do you do?

Dave: I work with heating and cooling systems. What about you?

Harry: Me? I’m a programmer.

Notice anything unusual? How do Japanese talk about their jobs?

山本さん: あの。。。田中さん、仕事は。。。?

田中さん: ええ。。。ボクは三菱ですけど。。。

山本さん: そうですか。すごいですね。わたしはトヨタです。

田中さん: ああ、トヨタですか。いいね。1

When Harry and Dave first talk about their jobs, what they do, not the company they work for, is what comes up. Even the language reflects that emphasis: “What do you do?” not “Who do you work for?” or “What’s your company?” Part of the reason is the traditional pattern of employment in each culture. Traditionally, Japan has had a system of lifetime employment: one joined a company after graduation and was employed by that company until retirement. One might be a manager, a salesman, and an engineer in those years, but one worked for the same company. On the other hand, Westerners generally continued in one line of work (sales, management, engineering, etc.) but changed companies several times in their careers. One might be an engineer first for Microsoft, then NEC, Dell, and finally Apple, but one would always be an engineer. The differences in how we speak here indicates very big differences in how Japanese and Westerners think about their work, their jobs, and the relationships between employees and employers.

Do not enter

You’ll notice that so far I’ve talked about “working for” a company and “employers.” Here’s another case where our language reflects differences in our thinking. The Japanese expression 会社に入る (kaisha ni hairu), translated as “enter a company,” sounds quite strange in English. The meaning would probably be misunderstood as walking into the company’s building or offices. Most Westerners don’t think of their relationship with the company that employs them in such an intimate way. Most wouldn’t even use the term “join a company.” The common expression “work for” accurately reflects the kind of relationship shared by most employees for their employers. It is a contractual relationship; the company pays you for some agreed upon service and time. The family feeling, while present in many companies, is not part of the basic relationship. Similarly, if one uses the expression “my company” in conversation, the other person is likely to assume that you are the company’s president or owner!

What’s my job?

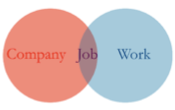

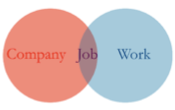

The employer-employee relationship is not the only difference in how Japanese and Westerners think about work. The cultural ideas about groups and individuals have a big impact on “work culture.” It is sometimes difficult for Japanese to make a clear distinction between their work, their job, and their company. For most Westerners, these are three very different things. The company is the organization that pays you for the work that you do. Your job is a general description of the kind of work you do. Your work is the specific set of tasks, actions, or outcomes you are responsible for. For example, Bill may work for Illinois Steel (company) as a sales representative (job), and his work might be taking care of accounts in the southwest area of Chicago (work).

The employer-employee relationship is not the only difference in how Japanese and Westerners think about work. The cultural ideas about groups and individuals have a big impact on “work culture.” It is sometimes difficult for Japanese to make a clear distinction between their work, their job, and their company. For most Westerners, these are three very different things. The company is the organization that pays you for the work that you do. Your job is a general description of the kind of work you do. Your work is the specific set of tasks, actions, or outcomes you are responsible for. For example, Bill may work for Illinois Steel (company) as a sales representative (job), and his work might be taking care of accounts in the southwest area of Chicago (work).

The most important difference to understand is that in the West, one’s individual responsibilities are very clearly defined. One’s responsibility rarely blends with those of others in a group. In the example above, Bill’s boss might be the sales manager for the Chicago area, overseeing five or six sales representatives. No one in the company would expect any kind of shared responsibility among Bill and the other representatives. If Bill’s sales are satisfactory, Bill will be rewarded; if they are not, he, and possibly his manager, will suffer the consequences. The other representatives share zero responsibility for Bill’s performance.

The most important difference to understand is that in the West, one’s individual responsibilities are very clearly defined. One’s responsibility rarely blends with those of others in a group. In the example above, Bill’s boss might be the sales manager for the Chicago area, overseeing five or six sales representatives. No one in the company would expect any kind of shared responsibility among Bill and the other representatives. If Bill’s sales are satisfactory, Bill will be rewarded; if they are not, he, and possibly his manager, will suffer the consequences. The other representatives share zero responsibility for Bill’s performance.

Again, these differences reflect the realities of the two different cultures. A Japanese worker, raised with the values of harmony and group cooperation, may find this kind of arrangement cold and intimidating. However, this kind of environment is precisely what a Western worker has been raised to live in. At the same time, a Western worker finding himself in a Japanese work environment would be frustrated at not knowing specifically the extent and limit of his responsibilities. He would also feel it unfair to be asked to help others in his group after he had successfully completed “his” work. Again, the ideas of groups and individuals pop up in many different situations.

Effort - Show it or hide it?

We have already looked at the different ways Japanese and Westerners treat guests (Chapter 4). The differences are somewhat similar to work-styles. As you might expect, Western work-styles are generally more casual than Japanese work-styles. However, be careful not to make the common mistake of thinking that a more casual approach means less dedication, less productivity, or less “seriousness.” If one looks at a worker in a different culture and tries to judge him by one’s own cultural expectations and values, huge misunderstandings are likely to occur.

Like the Japanese host, the Japanese worker knows that it is very important to appear busy, to appear as if he is working very hard, to appear to be making a great effort. This is true even if there is actually very little work to do. This is one reason why Japanese workers remain at their desks long after quitting time; even if “their” work is done, if their superior or their coworkers are still hard at work, leaving the office is rarely an option. Interestingly, almost the opposite is true in the West. There, the competent worker tries to look relaxed, in control, and to appear not to be working hard. Remember, in Western cultures, it’s generally better to be casual than formal, better to be relaxed than tense. If a Western worker were to always appear busy and working hard, his superiors would think that the worker was “out of his depth” and clearly unworthy of any future advancement. In the West, the ideal worker manages to do his own work and make it seem easy; this is the person who will most likely be chosen for advancement.

Like the Japanese host, the Japanese worker knows that it is very important to appear busy, to appear as if he is working very hard, to appear to be making a great effort. This is true even if there is actually very little work to do. This is one reason why Japanese workers remain at their desks long after quitting time; even if “their” work is done, if their superior or their coworkers are still hard at work, leaving the office is rarely an option. Interestingly, almost the opposite is true in the West. There, the competent worker tries to look relaxed, in control, and to appear not to be working hard. Remember, in Western cultures, it’s generally better to be casual than formal, better to be relaxed than tense. If a Western worker were to always appear busy and working hard, his superiors would think that the worker was “out of his depth” and clearly unworthy of any future advancement. In the West, the ideal worker manages to do his own work and make it seem easy; this is the person who will most likely be chosen for advancement.

This software advertisement shown at the right illustrates these ideas perfectly. The ad tells us that if we buy their software, we can be successful workers, just like the woman pictured in the ad. She is sitting with her feet up on her desk, smiling and relaxed, while her co-workers are hurrying around her. She is meant to symbolize the ideal worker–her work is finished and she has made it look easy.

These different systems create interesting work patterns. In Japan, workers stay in their offices late, and then often go out together afterwards. After all, they work for the same company, and are part of the same team. In West, and especially the U.S., it is extremely common for office workers above a certain level of responsibility to take work home. Almost every manager in the U.S. takes work home and has an “office” at home. He may chat casually with colleagues at the office, take long lunches, and leave the office early, but he will take work home with him at the end of the day to complete at home. Remember, casual is good, relaxed is good. However, if necessary, he may be up late or even all night in his home office, finishing “his” work, far from the eyes of his superior.

These are very good examples of how we can make big mistakes in thinking that behavior we observe in other cultures means the same thing that it does in our own. The Westerner looking for individual initiative and independence in the Japanese workplace will find very little; the Japanese person looking for dedication to the company in a Western work setting will be similarly disappointed. For some very surprising statistics about workers worldwide, download some files collected at <http://tonyinosaka.googlepages.com/workinghours.zip>.

Privacy and the Workplace - Don’t ask

The notion of individual privacy in the workplace is a very good indicator of how different the relationship between employee and employer is in the West. In the United States, when a person is applying for a job it is illegal for the company to ask the applicant his or her age, race, religion, politics, sexual orientation, marital status, marriage or childbirth plans, or even health (if it doesn’t affect job performance). This information is considered private; the only information an employer can ask for is information that has a direct effect on how well a person can do the work.

II. Comprehension Questions

If you have a difficult time answering these questions, read the passage again. If you can't find the answer, make a note of your question and ask the teacher for an explanation in your next class.

1. What is different about the two dialogs at the beginning of this chapter?

2. When we ask people about their jobs in English, we ask, "What do you do?" Why are those words significant?

3. Why does the expression "enter a company" sound strange in English?

4. How would an ideal worker in Japan and an ideal worker in America behave differently?

5. What kinds of questions are OK in a Japanese job interview, but unacceptable in an American job interview?

III. Thinking

New words and expressions

What are the main points in this chapter?

General summary of main points.

List some examples from your own life or observations that support these points:

List some examples from your own life or observations that do not support these points:

Your reactions and opinions:

1 It’s also obvious from this conversation that Mr. Tanaka is the sempai. Notice that in the English conversation, there are rarely clues to differences in status.

The employer-employee relationship is not the only difference in how Japanese and Westerners think about work. The cultural ideas about groups and individuals have a big impact on “work culture.” It is sometimes difficult for Japanese to make a clear distinction between their work, their job, and their company. For most Westerners, these are three very different things. The company is the organization that pays you for the work that you do. Your job is a general description of the kind of work you do. Your work is the specific set of tasks, actions, or outcomes you are responsible for. For example, Bill may work for Illinois Steel (company) as a sales representative (job), and his work might be taking care of accounts in the southwest area of Chicago (work).

The employer-employee relationship is not the only difference in how Japanese and Westerners think about work. The cultural ideas about groups and individuals have a big impact on “work culture.” It is sometimes difficult for Japanese to make a clear distinction between their work, their job, and their company. For most Westerners, these are three very different things. The company is the organization that pays you for the work that you do. Your job is a general description of the kind of work you do. Your work is the specific set of tasks, actions, or outcomes you are responsible for. For example, Bill may work for Illinois Steel (company) as a sales representative (job), and his work might be taking care of accounts in the southwest area of Chicago (work). The most important difference to understand is that in the West, one’s individual responsibilities are very clearly defined. One’s responsibility rarely blends with those of others in a group. In the example above, Bill’s boss might be the sales manager for the Chicago area, overseeing five or six sales representatives. No one in the company would expect any kind of shared responsibility among Bill and the other representatives. If Bill’s sales are satisfactory, Bill will be rewarded; if they are not, he, and possibly his manager, will suffer the consequences. The other representatives share zero responsibility for Bill’s performance.

The most important difference to understand is that in the West, one’s individual responsibilities are very clearly defined. One’s responsibility rarely blends with those of others in a group. In the example above, Bill’s boss might be the sales manager for the Chicago area, overseeing five or six sales representatives. No one in the company would expect any kind of shared responsibility among Bill and the other representatives. If Bill’s sales are satisfactory, Bill will be rewarded; if they are not, he, and possibly his manager, will suffer the consequences. The other representatives share zero responsibility for Bill’s performance. Like the Japanese host, the Japanese worker knows that it is very important to appear busy, to appear as if he is working very hard, to appear to be making a great effort. This is true even if there is actually very little work to do. This is one reason why Japanese workers remain at their desks long after quitting time; even if “their” work is done, if their superior or their coworkers are still hard at work, leaving the office is rarely an option. Interestingly, almost the opposite is true in the West. There, the competent worker tries to look relaxed, in control, and to appear not to be working hard. Remember, in Western cultures, it’s generally better to be casual than formal, better to be relaxed than tense. If a Western worker were to always appear busy and working hard, his superiors would think that the worker was “out of his depth” and clearly unworthy of any future advancement. In the West, the ideal worker manages to do his own work and make it seem easy; this is the person who will most likely be chosen for advancement.

Like the Japanese host, the Japanese worker knows that it is very important to appear busy, to appear as if he is working very hard, to appear to be making a great effort. This is true even if there is actually very little work to do. This is one reason why Japanese workers remain at their desks long after quitting time; even if “their” work is done, if their superior or their coworkers are still hard at work, leaving the office is rarely an option. Interestingly, almost the opposite is true in the West. There, the competent worker tries to look relaxed, in control, and to appear not to be working hard. Remember, in Western cultures, it’s generally better to be casual than formal, better to be relaxed than tense. If a Western worker were to always appear busy and working hard, his superiors would think that the worker was “out of his depth” and clearly unworthy of any future advancement. In the West, the ideal worker manages to do his own work and make it seem easy; this is the person who will most likely be chosen for advancement.