Materials

Clarinet bodies have been made from a variety of materials including wood, plastic, hard rubber, metal, resin, and ivory.

The vast majority of clarinets used by professional musicians are made from African hardwood, mpingo (African Blackwood) or grenadilla, rarely (because of diminishing supplies) Honduran rosewood and sometimes even cocobolo.

Historically other woods, notably boxwood, were used.

Most modern inexpensive instruments are made of plastic resin, such as ABS.

These materials are sometimes called "resonite", which is Selmer's trademark name for its particular type of plastic.

Metal soprano clarinets were popular in the early twentieth century, until plastic instruments supplanted them;metal construction is still used for the bodies of some contra-alto and contrabass clarinets, and for the necks and bells of nearly all alto and larger clarinets.

Ivory was used for a few 18th century clarinets, but it tends to crack and does not keep its shape well.

Buffet Crampon's Greenline clarinets are made from a composite of grenadilla wood powder and carbon fiber.

Such instruments are less affected by humidity and temperature changes than wooden instruments, but are heavier. Hard rubber, such as ebonite, has been used for clarinets since the 1860s, although few modern clarinets are made of it.

Clarinet designers Alastair Hanson and Tom Ridenour are strong advocates of hard rubber.

Hanson Clarinets of England manufactures clarinets using a grenadilla compound reinforced with ebonite, known as 'BTR' (bithermal reinforced) grenadilla.

This material is also not affected by humidity, and the weight is the same as that of a wood clarinet.

Mouthpieces are generally made of hard rubber, although some inexpensive mouthpieces may be made of plastic.

Other materials such as crystal/glass, wood, ivory, and metal have also been used.

Ligatures are commonly made out of metal and plated in nickel, silver or gold.

Other ligature materials include wire, wire mesh, plastic, naugahyde, string, or leather.

Reed

The instrument uses a single reed made from the cane of Arundo donax, a type of grass.

Reeds may also be manufactured from synthetic materials.

The ligature fastens the reed to the mouthpiece. When air is blown through the opening between the reed and the mouthpiece facing, the reed vibrates and produces the instrument's sound.

Basic reed measurements are as follows: tip, 12 millimetres (0.47 in) wide; lay, 15 millimetres (0.59 in) long (distance from the place where the reed touches the mouthpiece to the tip); gap, 1 millimetre (0.039 in) (distance between the underside of the reed tip and the mouthpiece).

Adjustment to these measurements is one method of affecting tone color.

Most clarinetists buy manufactured reeds, although many make adjustments to these reeds and some make their own reeds from cane "blanks".

Reeds come in varying degrees of hardness, generally indicated on a scale from one (soft) through five (hard).

This numbering system is not standardized ? reeds with the same hardness number often vary in actual hardness across manufacturers and models.

Reed and mouthpiece characteristics work together to determine ease of playability, pitch stability, and tonal characteristics.

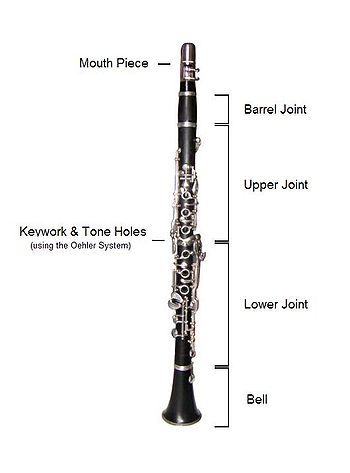

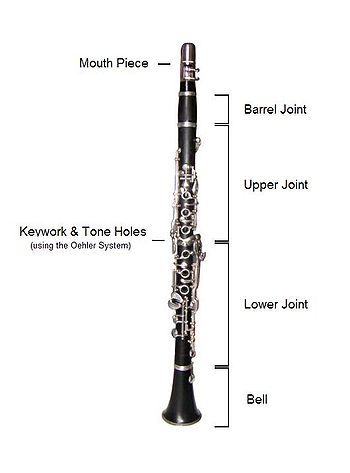

Mouth Piece

Mouth Piece

The reed is attached to the mouthpiece by the ligature, and the top half-inch or so of this assembly is held in the player’s mouth.

German clarinetists often wind a string around the mouthpiece and reed instead of using a ligature.

The formation of the mouth around the mouthpiece and reed is called the embouchure.

The reed is on the underside of the mouthpiece, pressing against the player's lower lip, while the top teeth normally contact the top of the mouthpiece (some players roll the upper lip under the top teeth to form what is called a ‘double-lip’ embouchure).

Adjustments in the strength and configuration of the embouchure change the tone and intonation (tuning).

It is not uncommon for clarinetists to employ methods to soften the pressure on both the upper teeth and inner lower lip by attaching pads to the top of the mouthpiece or putting (temporary) padding on the front lower teeth, commonly from folded paper.

Barrel

Barrel

this part of the instrument may be extended in order to fine-tune the clarinet.

As the pitch of the clarinet is fairly temperature-sensitive, some instruments have interchangeable barrels whose lengths vary slightly.

Additional compensation for pitch variation and tuning can be made by pulling out the barrel and thus increasing the instrument's length, particularly common in group playing in which clarinets are tuned to other instruments (such as in an orchestra).

Some performers employ a plastic barrel with a thumbwheel that enables the barrel length to be altered.

On basset horns and lower clarinets, the barrel is usually replaced by a curved metal neck.

Upper Joint of the Clarinet

Upper Joint of the Clarinet

The main body of most clarinets is divided into the upper joint, the holes and most keys of which are operated by the left hand, and the lower joint with holes and most keys operated by the right hand.

Some clarinets have a single joint: on some basset horns and larger clarinets the two joints are held together with a screw clamp and are usually not disassembled for storage.

The left thumb operates both a tone hole and the register key.

On some models of clarinet, such as many Albert system clarinets and increasingly some higher-end Boehm system clarinets, the register key is a 'wraparound' key, with the key on the back of the clarinet and the pad on the front.

Advocates of the wraparound register key say it improves sound and it is harder for condensation to accumulate in the tube beneath the pad.

The body of a modern soprano clarinet is equipped with numerous tone holes of which seven (six front, one back) are covered by the fingertips and the rest are opened or closed using a set of keys. These tone holes allow every note of the chromatic scale to be produced. On alto and larger clarinets, and a few soprano clarinets, some or all of the finger holes are replaced by key-covered holes.

The most common system of keys was named the Boehm System by its designer Hyacinthe Klose in honour of flute designer Theobald Boehm, but it is not the same as the Boehm System used on flutes.[21] The other main system of keys is called the Ohler system and is used mostly in Germany and Austria (see History).

The related Albert system is used by some jazz, klezmer, and eastern European folk musicians.

The Albert and Oehler systems are both based on the earlier Mueller system.

Lower Joint of the Clarinet

Lower Joint of the Clarinet

The cluster of keys at the bottom of the upper joint (protruding slightly beyond the cork of the joint) are known as the trill keys and are operated by the right hand.

These give the player alternative fingerings which make it easy to play ornaments and trills.

The entire weight of the smaller clarinets is supported by the right thumb behind the lower joint on what is called the thumb-rest.

Basset horns and larger clarinets are supported with a neck strap or a floor peg.

Bell

Bell

The flared end is known as the bell. Contrary to popular belief, the bell does not amplify the sound; rather, it improves the uniformity of the instrument's tone for the lowest notes in each register.

For the other notes the sound is produced almost entirely at the tone holes and the bell is irrelevant.

On basset horns and larger clarinets, the bell curves up and forward, and is usually made of metal.

Mouth Piece

Mouth Piece Barrel

Barrel Upper Joint of the Clarinet

Upper Joint of the Clarinet Lower Joint of the Clarinet

Lower Joint of the Clarinet Bell

Bell